By Solidarity Federation – LibCom.org

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are not the official position of the Bristol branch of the IWW and do not necessarily represent the views of anyone but the author’s.

If your only exposure to labour issues is through the torn and tattered pages of a greasy tabloid, you might be forgiven if you believe the TUC actually encourages workplace militancy. Full of contributions from beleaguered CEOs, scare-mongering columnists, condescending politicians and even tough-talking officials, you might even believe trade unions are an irrepressible engine of class struggle. For those us in trade unions, we know reality paints a far different picture. Far from encouraging and even organising industrial action, more often than not, trade unions leave militants feeling sold out, disempowered and sidelined.

Take striking for example. First, it’s a struggle to get a ballot. When the ballot is secured, it passes, but the union does nothing to effectively prepare for what amounts to nothing more than a symbolic one-day strike. In fact, other unions in the same workplace send out notices instructing their members to work on the day of the strike. At the last minute the bosses challenge the ballot on technical grounds. The union caves and calls off the strike. Management then presents a marginally improved offer which the union accepts with little or no consultation from the membership. Any chance of actual struggle is squashed by the same leaders who are supposed to be looking after our interests. In the worst case scenario, the bosses and the union come after shop floor militants who agitate against the settlement or who push for independent action.

The question is simple: why is the scenario outlined above (and countless ones like it) repeated again and again in every country around the world throughout the history of the labour movement? Is it a case of conservative, or even corrupt, leaders who sell the movement? Or is it something deeper?

Trade unions have long been subjected to critiques that seek to explain how and why “our” leaders act against the interests of their members. However, instead of simply analysing the structural reasons that unions are integrated into the management of industrial capitalism, we shall examine the words and arguments of the ruling class itself. In doing so we can come to understand to just what extent the bosses are conscious of—and consciously encourage—this process of integration and co-optation.

To do so we’ll employ the book How To Be A Minister. The author, Gerald Kaufman, is a long-serving Member of Parliament and is considered to be a right-wing member of the Labour Party. The self-described “most authoritative guide to the processes of government ever published”, How to Be a Minister has been recommended by successive incoming UK governments since its first printing in 1980. We’ll be concerning ourselves with chapter 13, “How to Work with the Unions”.

In short, Kaufman’s argument is a simple one: legislators and trade unions—and particularly their national leadership—should work closely with government to resolve and, more importantly, prevent industrial unrest. Of course, radicals have long argued that the role of unions are to help the ruling class manage class conflict and secure ‘industrial peace’ by ensuring disputes stay within the realm of the state-sanctioned and regulated ‘labour relations regime’. For the unions, resolving disputes in such a manner ensures they maintain their legitimacy as privileged, representative bodies entitled to negotiate the sale of labour power. The beauty of Kaufman’s book is how he demonstrates just how keenly government and industry are aware of these dynamics.

To explore this, we’ll examine five excerpts from How To Be A Minister. The first quote, as we shall see, lays out a general vision for the roles of unions, industry, and government in contemporary capitalist society.

It makes sense for governments and unions to work together. The unions represent millions of organized workers; their assistance can eliminate problems which might have caused trouble and make easier for governments the solutions of problems that do arise, while their opposition may make existing difficulties worse and create confrontations that co-operation could have prevented altogether.

While neoliberal reforms have gone a long way towards impinging on the tennets of social democracy which used to be a bedrock of British society (and which were certainly still in place when Kaufman released the first edition of his book), the framework of social democracy still largely determines the relationship between employees and employers Britain. The rolling back of the ‘post war consensus’ may have eliminated some of the privileges enjoyed by the TUC, but this has not prevented its member unions from vocally espousing a model of organisation based on cross-class social partnership. For even those unions who employ selective militancy and use the language of social conflict, the reality of representative negotiation, collective bargaining agreements, and trade union legislation means enforced social partnership is part-and-parcel of the normal functioning of trade unionism. Union disputes—often symbolic and with little organisational support from the national union—don’t change this dynamic.

Kaufman’s first quote clearly reflects this reality. It acknowledges the power of “millions of organised workers” who are represented by trade unions. “Their assistance”—meaning union officers, not workers—is needed to prevent “trouble” and “confrontation.” This is the very logic of mediation. One is reminded of a quote from a South African industrialist describing why he chose to recognise the union in his factory:

“Have you ever tried negotiating with a football field full of militant angry workers?”

Kaufman applies the same logic, only he does so on a national scale.

We ministers at the Department of Industry had it made clear to us by the national leadership of the unions with which we were involved that it would be deeply resented if we saw groups of shop stewards at our department without their agreement. …As one of the very left-wing leaders of one of the most left-wing unions put it to me: ‘I’m having no rank-and-fileism in my union.’

Besides the fact that shop stewards don’t have any business sitting down with MPs, the above statement does give us insight into the internal functioning of unions and—more importantly—why they function in such ways. Trade unions, despite rhetoric or even best intentions are, by nature, bureaucratic, centralized, and hierarchical. In fact, they must adapt these characteristics if they wish to fulfil their role as representative, mediatory bodies. The fact that labour law also demands such a structure is secondary.

Besides damaging internal democracy, such a structure creates a situation in which the officialdom has a different set of interests from the membership. This is especially true with paid full-timers and officers on full ‘facility time’, but even branch-level officials are not immune from this dynamic.

This contradiction, again, is determined by the role of unions as mediators between labour and capital. Unions officials are expected to be ‘responsible leaders’. This includes ensuring workers ‘stick to their half of the bargain’, follow the union-negotiated collective agreement, and stay within the bounds of labour legislation. If they fail do these things, the leaders’ privileged role (which, on the national level, includes six-figure salaries) as ‘representatives of organized labour’ is compromised. Union assets will be frozen, leaders could be jailed, and the bosses—with whom the ‘social partnership’ has been struck—will have no incentive to continue to recognize or negotiate with the union.

All of this is a roundabout way of bringing us to one of our most fundamental points: trade unions are mediators of struggle. Workers go to the union representative when they have a problem at work—be it legal or contractual—and the role of the rep is to see it rectified. The union is the bargaining agent with whom the boss sits down with to resolve grievances or sign a new collective agreement. Likewise, when industrial action occurs, it is done through the union and the union takes responsibility for balloting and ensuring all legal procedures are followed.

In theory, this doesn’t sound too bad. However, to be able to effectively do the tasks outlined above, the union must be able to ‘speak’ on behalf of the workforce and ensure that what it says of its membership will happen. For example, if workers vote to take industrial action, but the court grants an injunction against striking, the union must ensure workers don’t take action. If the workers do strike, it is legally held responsible for the workers’ actions.

Beyond the legal imperative to control their members, the ability to turn off struggle is necessary if the union negotiators are to maintain credibility with the employer. So if the workers have voted to strike, but the officials feel management’s new position constitutes an improved offer, the union officials must be able to guarantee the strike won’t happen. If it does, management have no incentive to continue to negotiate with the union. All of this is a way of saying that in order to mediate struggle, unions must be able tocontrol struggle. And that’s the problem.

Hence, we return to this unnamed “very left-wing [leader] of one of the most left-wing unions” and his overt opposition to “rank-and-filism.” Union leaders, even self-proclaimed militant leftists, need be able to control the actions—and even the words—of their membership. It’s Kaufman’s service to us, as rank-and-file militants, that he has laid bare this basic truth.

Heath’s conservative government might have survived long after 1974 if its Secretaries of State for Trade and Industry had regular meetings with the [leaders of the National Union of Miners] well before trouble broke out. You cannot suddenly construct a close and trusting relationship during a crisis.

Radicals have often described the trade unions as ‘relief valves of class conflict.’ Despite what politicians, business leaders, and the media publicly state, the ruling class is fully aware of the conflictual nature of capitalism. “Trouble” and “crisis”, as Kaufman labels it, are inevitable elements of class society. In an effort to reduce the scale and scope of these conflicts, capital has sought to find orderly means to resolve worker unrest. Trade unions, with their hierarchies, by-laws, and ‘respectable leadership’ have, historically, have been a very effective means to achieve this.ii For bosses and the state, the legalisation and institutionalisation of trade unionism also creates the impression that, for workers, the only option for struggle is through the unions. Trade unionism discourages and limits the scope for workers’ self-organisation and, instead, posits the TUC as the legitimate body to speak on behalf of the working class and organise the ‘official action’ that is supposed to further our interests as workers.iii

The prolonged period of class conflict roughly encompassing the two world wars resulted in a social democratic class compromise which saw this process taken to its logical conclusion. Trade unionism became integrated into the very structure of capitalism.iv The manifestations of this are clear: the trade-union sponsored ‘Labour’ Party; binding state-sponsored arbitration; ‘management rights’ and no-strike clauses in collective agreements; and the demand that unions prevent, “repudiate”, and rectify ‘unofficial’ industrial action. This is not to even mention management-union collusion in disciplining and even sacking troublesome rank-and-file militants. There is, of course, a trade off for the TUC in this bargain. They are granted a protected status as negotiators of the sale of labour power and steady dues streams as officials hob-nob with the very business leaders who are their supposed adversaries.

Building on the historic role of unions, Kaufman’s message to legislators is simple: get union leaders on side and “construct a close and trusting relationship.” When crises occur, this pre-existing relationship will ensure they are receptive to your argument and not, say, pressure from militants within their membership.

The unions may ask to see you about preventing closures in their industry [which you will have to inform them] cannot be stopped….

[Speaking from personal experience in a similar situation] the unions’ leaders were, however, truthfully able to tell their members they had tried every possible way of saving their jobs; very important when one of the problems in trade unionism in recent years had been to maintain links between the national leadership and the rank-and-file.

Here we have another nugget of truth; namely, that capital and government are very aware the division between the union officialdom and the rank-and-file. Moreover, it is parliamentary policy to not only placate union officials, but to do so in such a way which shores up the leadership’s supposed legitimacy in the eyes of the membership.

There is another sleight of hand here. Kaufman writes that union leaders could “truthfully” tell their members that “every possible way of saving their jobs” had been tried and exhausted. This is, of course, plainly untrue. There had been no attempt made at organising industrial action and certainly no attempt made to spread struggle across and between industries in solidarity. Yet the same line is held by the politician and the union bureaucrat: ‘We, your representatives, we’ve done all we can to save your jobs. The struggle is over, but do make sure to vote for us next time an election comes round…’

Trade unionism has had its bad periods in Britain but, far more often than not, it has been a force for sanity. …[So stay on good terms with the trade unions because,] by doing so, you may achieve successes that otherwise would have alluded you. And you may avoid disasters that no one will ever know might have happened.

Such sentiment has been expressed time and again not only by politicians but business associations, HR departments, and trade union leaders around the world. And of course such individuals want “a force for sanity” against raw, unfiltered class antagonism. Capital understands the conflictual nature of industry. Management training courses often read like Marx in reverse, teaching managers how to deal with the conflict inherent to the workplace.

Trade unions, with their reps and hierarchies, are a fantastic means to channel worker discontent. Throw in a labour relations system based on ensuring all disputes happen through strictly regulated framework and a highly-paid union leadership based not on the shop floor and trade unions become a very attractive options for handling industrial relations. This does not mean, of course, that in low points of class struggle bosses won’t try rid themselves of unions. However, once the prospect of unruly self-organised struggle becomes a real threat, the “sanity” of the trades unions becomes another tool for the bosses to “achieve successes” and “avoid disasters”.

Conclusion: Self-organisation and Self-representation

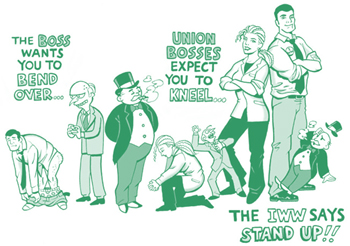

This article shouldn’t leave readers with the impression that workers shouldn’t be organised. The concept of a union—one or more workers sticking together to improve their lives at work—is fundamental to not only improving our lives today but in eventually creating a new society free of exploitation. However, once any labour organisation takes on certain roles of mediation and representation—in a word, trade unionism—the problems begin.

We don’t believe today’s trade union leaders are bad people or even “sell outs”. Trade unions and, by extension, their leaders, are trapped by their role as mediators of struggle. As much as managers have to make decisions based on the needs of profit and budgets, the trade union leadership has to make decisions based on mediating the inherent struggle between the working class and the employing class.

As has been outlined, inevitably there will be a point in struggle when union leaders will be forced into making decisions that not only run counter to the interests of the working class, but attempt to repress the revolutionary impulse of the proletariat. This may come, as in Paris 68, when Communist union leaders called for workers to evacuate their occupied factories and sought to transform a revolutionary situation into a wage dispute. Or it may take place long before that when union leaders disavow wildcat strikes and do everything in their power to keep them from spreading. In any case, “our” representatives are inevitable trapped by their role as representatives and mediators. With this dynamic in mind, we cease to see militant leaders, improved democracy, or reform of labour law as the solution to the problems within mainstream union movement. Instead, we come to realize it is the trade union form itself that is the problem.

Such perspectives are important now that class conflict is back on the table. The trade unions, for their part, are already attempting to leverage the the threat of uncontrolled working-class self-organisation. As disputes over cuts were heating up, TUC general secretary Brendan Barber issued this warning to the Tory-led coalition government in relation to tightening up anti-strike laws:

“If they do try and change the law the Government would run a real risk of provoking more groups of workers to think ‘We’ll go down different routes – we won’t have ballots. We’ll carry out wildcat responses.’ That would make strikes much more difficult to deal with.”

Yet there is another option beyond a re-run of the sad history of co-optation and defeat. It is to take Brendan Barber’s advice: Go down a “different route”, don’t “have ballots”, and make “strikes much more difficult to deal with”. Should this occur we can expect situation where capital again declares “We must give them reforms or they will give us revolution.”v Yet, we know where those reforms led and the legal backing given social democratic trade unionism has proven to a be a tool for diffusing working class anger and organisation.

Instead we must build up the capacity to “go down a different route.”

We—meaning the Solidarity Federation—don’t claim to have all the answers and, in any case, mass struggle always throws up its own forms of self-organisation. However, we are consciously trying to build a self-organised workers movement. We do this through the creation of independent ‘workplace committees’ made up of militant workers who seek to identify winnable workplace grievances and tackle them through direct action. By building on small victories, we grow our committee, and take on larger grievances. These committees link through industrial networks to share tactics, develop strategy, and eventually begin taking on industry-wide issues.

The other advantage to this committee model is that it gives us, as revolutionaries, a way to reach out to and organise along our non-radical workmates. If folks join SF in the process, great! Fundamentally, however, it is this struggle—based in the workplace and around material conditions—which politicises workers and provides us, as radicals, the space to begin talking about capitalism and class struggle.

—-

i. This is not to say that unions won’t use the threat of unofficial action as a bargaining chip, but this doesn’t change the fundamental dynamic: the “responsible” leadership is there to ensure that unless management bargains with them, the employer will face the prospect of dealing unpredictable and volatile workforce on their own.

ii. This is not to say that when the balance of class force makes it seem advantageous, bosses won’t try to break unions. Yet, when class activity heats up, those same bosses turn to the trade unions as one of the main weapons in the arsenal of control.

iii. It’s probably worth noting her that unofficial industrial action is not illegal, it’s “unlawful”. While this may sound like a semantic distinction, it means that workers lose legal protections for their action, but it’s still only a civil matter. Of course, legality is merely a veneer for the state and there’s no doubt that if industrial unrest reaches a certain point state violence is a real possibility.

iv. None of this was new, of course. Trade unions—far from the radical organs portrayed by the most sensationalist sections of the ruling class and capitalist media—have never been revolutionary vehicles. The practices of mediation and co-optation weren’t invented as part of the social contract, it merely enshrined what was a pre-existing and ongoing process.

v. Tory MP Quintin Hogg’s 1943 suggestion on how to deal with increasing working-class militancy.