In late September 2017 the IWW London branch invited friends and comrades to take part in an organising drive in West London factories and warehouses. We chose half a dozen companies, employing between 100 and 800 mainly migrant workers where there was no trade union present.

Shift-changes, London’s western logistics corridor and the Wobblies – A preliminary summary of an IWW organising effort, winter 2017/18

Dedication

Dedication

This text is dedicated to our friend, comrade and fellow worker Peter Ridpath, who died on April 8th, 2018. Peter was a kind and dedicated member of the IWW London Branch and came out to support us in west London many times. Born in East London in 1948, Peter was a genuine working-class militant. He went from school into a series of factory and labouring jobs with spells of unemployment where he read voraciously, mainly on literature, history and politics. He became a bookseller and organised his co-workers. In his retirement Peter supported many strikes and pickets, especially the actions of the Sparks, a rank-and-file network of building workers.

Peter joined the IWW in 2009 and quickly became an indispensable part of the branch, holding a variety of positions and taking an active role in the life of the organisation. But more than his formal union work, he’ll be remembered for his dedication to making a better world, something that Peter embodied in his personal and political life. His warmth and personality made him universally popular, liked and respected by all. He had that rare combination of kindness and intellect that never failed to bring a smile to the face of everyone around him.

Here’s to you, Fellow Worker. Rest in power.

Synopsis

“The security came straight away after we had set up our table and flags. They complained about the stickers we put up last time and that they had damaged private property. They called the police who said it was ‘civil trespass’ and moved us on. I googled ‘civil trespass’ and it says this is only the case if it is an ‘unjustifiable intrusion’ – which obviously is pretty subjective! Some legal advice would be good here because no doubt we get confronted by the snouty-snouts again.”

In late September 2017 the IWW London branch invited friends and comrades to take part in an organising drive in West London factories and warehouses. Members voted for this as London IWW’s strategic focus for 6 months. We chose half a dozen companies, employing between 100 and 800 mainly migrant workers where there was no trade union present. Comrades from the West London AngryWorkers collective, who have been active in the area since 2014 provided some insights and a few contacts within these companies. The response to our invitation was positive and we were able to welcome around two dozen new friends to the campaign.

We organised a day-school where we learnt more about the area, the background of the local workers and the specific conditions in each of the companies. We formed half a dozen teams which were to focus on one company each. We discussed the first leaflet with which to address the workers, how to introduce ourselves, and what to ask and look out for during our first visits at the gate.

Over the following months we managed to organise four, five visits at each of the companies and distributed hundreds of leaflets, many of them translated into three or four different languages. We established closer contacts with some of the workers, often by supporting them with individual grievances. We learnt a lot, last but not least that under the general condition of fear created by migration policies and the factory regime, ‘organising successes’ are not easy to come by. Particularly in the food processing and logistics sector, which is hidden away from the public and dominated by so-called ‘unskilled’ and often female labour and crossed by language barriers.

But there were moments of promising energy, for example when over 20 workers from a sandwich factory turned up in a Somalian community centre; when they told us about the actions they had already taken and the steps they hoped to take in future. We had the joy of witnessing mainly South Asian factory workers listening to the stories of cleaning workers from Latin America, how they had resisted management and won the London Living Wage at the Ferrari showroom in central London. In the following summary we will focus on this experience with the sandwich factory workers to explain the possibilities and problems of our organising effort.

From a quantitative point of view the organising campaign might seem unsuccessful: after six months of activity we managed to sign on only a dozen or so new members. In only two cases management made concessions to workers, e.g. paying an extra-bonus, in response to the stir the union created. As participants in the effort we would still like to emphasise the positive result: we got deeper insights into the local conditions, we got to know many workers with whom we will stay in touch in future and we spread the word of a different kind of union amongst hundreds of working class people who might remember us when the time seems ripe for them. In this sense the organising and learning continues.

We would therefore still encourage fellow workers to take a step across the border and try out similar things. Below you can find a more detailed account of our experience. Any comments, criticisms, questions are more than welcome.

For the One Big Class Union

IWW / AngryWorkers

westlondon [at] iww [dot] org [dot] uk

www.iww.org.uk

www.angryworkersworld.wordpress.com

www.workerswildwest.wordpress.com

1. Why did we chose factories and warehouses in West London – what are the general conditions?

2. What was our general organising approach and concrete plan for this campaign?

3. Main example: experiences at A1 sandwich factory

4. Conclusions and open questions

5. Appendix: Short summary of the reports after team visits at the other companies, leaflets, pictures

——

1. Why did we chose factories and warehouses in West London – what are the general conditions

What was the constitution of the IWW London branch at the time when we decided to focus on the West London organising campaign?

The branch has around 250 members, though only around 20 to 30 fellow workers take part more actively e.g. by coming to the branch meetings. There is a cleaners’ branch which survived the initial split with the IWGB, but apart from occasional repping the GMB is less involved in the cleaners’ business. The main focus of the branch is on rep and organiser training and on the situation in workplaces of a few individual members, mainly the teaching sector, charity sector or hospitality. In this sense the branch was stable, but the ‘organising where we are as members’ didn’t create a wider dynamic, partly because of the composition of the branch (unemployed/retired, freelance, smaller workplaces). In this sense, focusing on bigger workplaces in West London was a jump into cold water and less of an organic development than a strategic decision. This was facilitated by the fact that the AngryWorkers collective – most of them IWW members – have been working and informally organising in the West London area since 2014. Informal structures like workplace groups and solidarity networks attracted a limited number of workers, perhaps also because 90 per cent of local workers have a background of recent migration. Would the idea of a union – a form of organisation that many people would be familiar with – give workers more confidence to act? We thought it was an experiment worth trying. Apart from a general knowledge about the area and basic contacts within the specific companies, AngryWorkers were able to help out with sleep-over sofas for early morning starts and community centre space provided by a local volunteer run charity organisation. They also organise weekly solidarity network drop-ins in the area that we could refer individual workers to.

What are the main conditions in the West London logistics and industrial area?

The area is part of the so-called western corridor, which stretches from Heathrow to Park Royal and contains the M4 and A40 as the main logistical axis. Attached to Heathrow airport there are a lot of warehouses and a fair amount of fruit, veg and other raw material comes in through the airport. In total there are around 80,000 workers employed in and around Heathrow. Recent studies say that 60 per cent of the food consumed in London is distributed, re-packaged or processed in the western corridor. Apart from Heathrow area there are various industrial estates in Southall (10,000 workers), Greenford (10,000 workers), Perivale (5,000 workers) and Park Royal (30,000 workers) – most of the companies we targeted are situated in these industrial zones – within an eight mile radius. There are only few workplaces employing more than 1,000 people. The workplaces we focused on range between 100 and 800 workers. Most workers in the area are on the minimum wage or slightly above and many workers are either employed through agencies or on zero-hour contracts. Working weeks of 50, 60 hours are the norm. Only few companies actually do things that infringe the labour law e.g. most pay the legal minimum, which means that unlike in, for example, the logistics sector in Italy it is not easy to mobilise people by pointing out that we have to ‘fight for our rights’.

Most workers are migrants, visa status is a big issue and migration raids in factories and warehouses are common. Around half of the workforce is from Eastern Europe, the other half from South Asia (workers from African countries are in a minority). This means that Brexit or the Windrush-‘scandal’ hang over workers’ heads, as possible threats to their future in this country. This also means that workers don’t come from regions with recent experiences of struggle, such as in South America or the countries of the so-called Arab Spring, which influenced migrant workers’ struggles abroad, e.g. the logistics workers in Italy. In food processing and small-scale manufacturing most workers are women, harassment in the workplace is rampant. Inside the factories the sexist division of labour is obvious, e.g. women work on the line, have the most stress and lowest pay, while men tend to get the easier jobs or supervisory positions. Workers tend to live close to the workplace, many of them in Wembley (Gujaratis), Southall (Punjabis, Somalis) and Greenford/Ruislip (more Eastern European). Most workers live in shared flats, many share rooms. There are only very few social spaces for mingling after work: temples tend to play a role, or standing together drinking beer.

In many places it is difficult to talk at work (line work, machine work, productivity targets), either because of the nature of work or the strict surveillance. Job rotation is high amongst the young and more rebellious (male) workers. Many people have arguments with supervisors, don’t show up, rebel individually and are sacked. Many find something better after a short while, as it is not too difficult to find work. People who stay in the job longer tend to get depressed or submissive, often because they have lower prospects on the labour market, e.g. non-english speaking, ‘unskilled’ women. Our experiences with existing unions are dismal: in many bigger workplaces we find GMB, USDAW or UNITE representation, but mainly for the permanent workers or completely tied up with management. Workers general view on unions is negative, either because of direct experiences or background (e.g. Solidarnosc sell-out in Poland). We needed to keep that in mind when introducing ourselves as members of the IWW union. At the same time, ‘strike’ and ‘union’ seem the main thing people come up with as the solution to their workplace problems. When ‘strike’ is portrayed as the main thing to do, then the bar ‘to do something together’ is set very high, also in order to explain why someone is afraid to do anything. We wanted to emphasise that there are other possibilities to take action at work (work to food hygiene standards, warehouse health and safety, refuse overtime etc.). When it comes to organising, the so-called ‘social leaders’, in particular amongst the South Asian workers, tend to be patriarchal figures who easily are pushed into middle-men positions (union reps, supervisors and in many cases both), and can’t just be ‘used’ as organic organisers.

We think it is important to organise amongst these workers for various wider and political reasons. Individually these workers are amongst the weakest, but their collective potential is amongst the most powerful, as they keep London and its financial centre ticking over. The political climate directly impacts on workers confidence (Brexit etc.) and any resistance from their side can change the social atmosphere. These workers can’t defend ‘their professional status’ as they are ‘unskilled’ workers. This would make it easier for any struggle to generalise: workers share the main experiences of being bullied at work, low pay, insecure status etc. – in a world of modern technology, from voice-control picking via a headset, to hand-held scanners to GPS systems used in delivery vans. Struggles amongst these workers can make visible how modern cities are run and what they depend on (circulation of goods, food supply). To organise in the western margins of the city will be much harder than organising amongst migrant workers in places like SOAS, LSE etc., as the companies have no name or major reputation that could easily be damaged. There is no leftist scene around, like on campus. The areas are remote and outside of the public spotlight. We have to bear this in mind when mobilising people.

2. What was our general organising approach and concrete plan for this campaign – report from the initial day school

Based on our knowledge about the general conditions we chose seven, eight companies to focus on. The main commonalities were that they are in the logistics of food processing/light manufacturing sector, employing between 100 and 1000 mainly migrant workers and with no union presence. Although we knew workers in some of the companies, they were not willing to take over an active organiser role, mainly because of fear of management repression. In terms of our approach we discussed that we want to take the lead from the workers and first see where they are at, what they might have tried themselves, what they see as the main hurdles when it comes to challenging bosses’ power. We knew that we would have to deal with the major structural pressures that exist outside of the workplace but impact on workers’ confidence: the migration regime, the family structure. In this sense our main aim of the organising effort was to help with building any kind of collective structures that help workers’ confidence at work and beyond the workplace. We were not focused on membership recruitment as such. At the same time we also made it clear that if a certain amount of workers would formally join the IWW we could enter a legal wage dispute with the company, meaning, we tried to link membership to a concrete medium-term goal.

Apart from this we saw the organising campaign as a way to gather new experiences helpful not only to the IWW, but the revolutionary left in general. We were inspired by the way that migrant warehouse workers in Italy managed to re-focus the otherwise rather sectarian left on class struggle and its practical necessities. We hoped that the engagement with migrant workers at the margins of town could make a useful contribution to a largely middle-class left in London, which has lately focused more on the stage-show of Labour and parliamentary politics rather than on working class self-emancipation. We organised various film screenings and talks to invite people to take part in the organising effort as we had decided that this would be a public campaign, open to all, regardless of whether or not you were in the IWW. We got a very good response, mainly from students who had gathered experiences during the struggle of outsourced workers on their university campuses. In total around 25 people joined us in the campaign, out of which only around a quarter were actually IWW members. While the teams had a good gender balance we lacked people who shared a similar language background as the workers, which posed a considerable problem. All in all, the organising effort was a good and largely self-organised collaboration between people of various groups, from Solfed to Plan C to UVW, and a lot of people who haven’t been members of any particular group before.

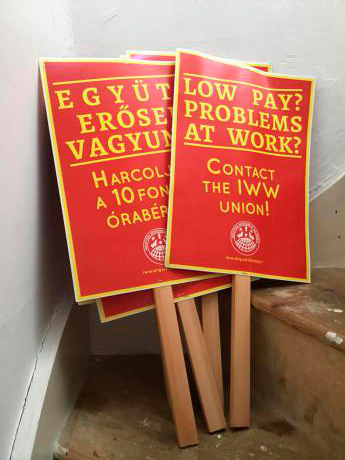

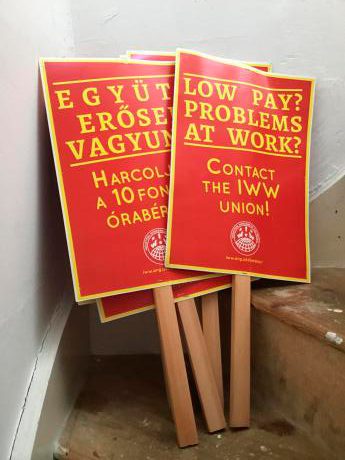

We started the campaign with a day-school where we shared knowledge about the area and workplaces, formed teams for each company and developed a rough workplan. Each team of four to five people was meant to research additional information on their respective company and write an initial leaflet. The leaflet should address company specific problems we already knew about, ask workers directly about additional problems and introduce the IWW as a workers-led union. During the first team visit additional information and first contacts should be established, followed by an – ideally! – weekly presence at the gates over the following weeks. Each team elected a coordinator who was responsible to report back to the whole organising campaign after each visit, in order to share information about what worked and what didn’t. We tried, when possible, to support individual workers with their problems, also in order to build up some reputation. The initial leaflet was then modified, newly gathered information added. After four months we organised a first review meeting where all the teams came back together. We also tried to organise a bigger presence – a ‘show of force’ – at each of the companies, to demonstrate to workers that if necessary we could mobilise more than the four, five team members. The organising campaign was fairly horizontal and unbureaucratic, basically relying on personal relationships inside the teams and a mailing-list for coordination. We managed to visit each of the seven, eight companies up to five, six times – distributing hundreds of multi-lingual leaflets, all on a budget of £100 or so. We could have done with more face-to-face meetings amongst ourselves and more frequent visits – but that is London for you, many team members travelled one or two hours from the other end of town. Read the concrete company reports below – followed by a more detailed description of our experiences at the A1 sandwich factory.

3. Main example: experiences at A1 sandwich factory

We got a very positive response from workers of a local sandwich factory and were able to organise two meetings with over 40 workers. We therefore want to give a bit more space for the description of this experience.

/// General conditions

A1 is a major sandwich supplier for the main supermarket chains. People in the UK buy around four billion sandwiches a year, a big and labour intensive business. Despite its seemingly ‘home-made’ character the sector is dominated by a few bigger corporations, e.g. Greencore (another company we visited during our campaign) and 2 Sisters produce around a quarter of the national demand. There is currently a fair bit of restructuring going on; A1 recently closed a plant in Middlesborough and shifted production. In factories like A1, 300 to 400 workers can produce 250,000 sandwiches and more per shift. The work is tough, there is little automation, most work is done on conveyor belts. Workers stand on one spot in the chilled environment and repeat the same work-step every 5 seconds. Most of the workers at A1 are from South Asia and Eastern Europe (Lithuania in particular). There is a lot of bullying pressure from management, something systemic in the ‘low-skilled’ industrial and logistics world. Workers also face frequent workplace raids by the migration police.

/// First visit

The first visit was tough: security called the police and tried to stop us talking with workers. He even told workers, “You’ll get into trouble for talking to them!” He was a total pain, but we stuck it out and put the flags away. We hid in a shop opposite until it get a bit darker and then attempted to talk to people again. Security threatened to call the police again, but even if he did call, they didn’t show up again, knowing it was not a serious issue. Hurray for police cuts! Some of the workers we talked to were angry, rather than intimidated: “How dare they wanting to decide who we can talk to or not?!”

When we first visited A1 we had no direct contact – a friend of ours had worked there as a cleaner, but that was a year ago. The first surprise was the amount of workers who are employed at the factory – from short reports and the size of the building we guessed it was around 300, but it turned out to be more like 800 plus agency workers. The second surprise was the response from workers that went beyond a merely positive attitude towards the idea of a union: people were eager to put down their phone numbers and promised to turn up for a meeting. In general their level of English was better than the local average.

“K spoke to a forklift driver, who gathered several other men working in goods-in. She spoke to them for a long time considering they were on shift – they didn’t seem afraid of managers. Some of them even took leaflets and started giving them to other workers. They said they had tried asking for higher wages individually but it didn’t work: last year they only got an insulting £0.04 pay rise. They, too, were mainly Punjabi and keen to form a union. When they brought up the issue of victimisation, K said this is the reason why “there shouldn’t be visible leaders”, so they can’t go after just one or few people – they were very receptive to this and said, “everyone should be a leader”. She also told them they can go the “legal” route of getting 10% membership, or find other ways to put pressure on management but that we would need a meeting of workers from across the factory to discuss our options.”

“The supervisor of the warehouse – Albanian guy – is sound. He said that he had fought with management to get everyone in the warehouse at least £8.85. Hygiene guys in the factory are still at £8.50, whereas the production workers only get £7.50 (at least the agency folks). He also said that management promised pay increases several times, but never gave one.”

After two or three trips to A1 someone called us directly to ask us when exactly the meeting would be. He said many people were interested in coming. We promptly set a date and place (a Somalian community centre in Southall) for the following weekend. We contacted others whose details we had and let them know.

/// First meeting

We prepared a rough structure for the meeting, not knowing exactly how many people would attend:

* What is the IWW, what is our approach, what do we do in the area;

* Each worker should introduce themselves, where they work, what their main grievances are, what they already tried to do about it;

* How to talk to and involve more co-workers in future meetings.

Around 20 workers were present at the meeting. Apart from two Lithuanian women it was mainly workers from an Indian background. Around three quarters were women – although they had initially used a guy to contact us to set up the meeting. Most workers were from the production department (production operatives, staffers and quality controllers), one worker worked in hygiene/cleaning. Apart from two workers everyone had worked in the factory for more than two years. Goods-in workers were on shift, but some of them also announced interest. Most of the time was taken up by workers’ description of the situation in the factory.

During our first meeting with A1 workers did most of the talking. They were keen to tell us about the general conditions and their major grievances:

* Minimum wage of £7.50 for most workers on the assembly lines who prepare the food; after working for the company for 5 – 10 – 15 years; only 30p more for nightshift and quality control workers;

* No regular working hours even though most are permanent staff. They never know when they will finish work – it could be 4pm or 9pm, which makes childcare and family responsibilities difficult to juggle;

* Overtime is paid at single rate for most workers, at 1.5 for workers with older contracts;

* When orders are down, they are told they have to take the day off as holiday with no notice period;

* They get one half an hour break and one 15 minutes break during the shift which can sometimes last as long as 14 hours. If they stay for ‘overtime’ they do not get an extra break;

* Break times are also rushed because the time it takes to get through the changing room and into the canteen is part of the total time allowed for the break. So in reality, break times are even less than this;

* It is cold in the food prep area where workers stand for 8-14 hour shifts.

* About 20% of workers are on the old ‘Superior Foods’ contracts, the rest are on the newer ‘Food Partners’ contracts (there was a merger some years ago). People on old contracts get higher overtime payments and paid breaks.

* Around 60 agency staff. They have worked there for years, have the same conditions as the Food Partners people and get offered contracts when the company needs more workers. The relationship between permanent and agency workers is good.

* Main nationalities are Indian (Konkani and Hindi speakers), Lithuanian, Romanians, Poles.

* December and the period May to June is less busy, due to school holidays.

As we were to find out, workers had already undertaken various collective steps themselves:

* People want to work overtime because this is the only way to make ends meet. But their situation is being exploited by bosses who are getting away with paying their workers peanuts. One time, when some women workers decided to stay for overtime they asked for a third break after 10 hours. Managers refused. So workers on two lines got fed up and all clocked out at the same time. The next day, nobody said anything to them about leaving.

* Because it is food production it is cold in the factory, plus things are transported in and out, so it is also drafty. The uniforms that are given to workers don’t protect them from the cold and the rubber boots are often way too big or small. Shopfloor managers ignored many complaints about this. A group of a dozen workers had enough and went straight to the office of the main factory manager to demand better uniforms. This caused a big stir, the shopfloor manager screamed their head off, but things got moving.

* Three maintenance workers got together and engaged a solicitor to write a collective grievance about being down-graded as ‘maintenance operatives’ after having worked as technicians for several years.

* Workers individually refused to sign the new contracts (from Superior Foods to new A1 contracts). After complaints, management held a meeting last year where they promised to equalise the conditions between different contracts, but nothing happened afterwards.

* Workers decided to come together and write a letter to management about the short breaks, irregular shifts and long hours that left no time for family and a life outside work. Around 90 workers signed it, from all language groups, both temps and permanents. Management tried to invite single workers for a meeting, but initially workers were clear: “This is an issue affecting of all of us, so speak to all of us”. Workers insisted on at least 3 workers attending. Three of them did go, but it seems the meeting had no further results.

* We wrote up all the grievances they raised and handed them out to workers during the second meeting (see appendix);

* We decided not to ask people to sign up to the IWW at the first meeting, but to first try and create a working relationship;

* We decided to make a clear visual plan of the next steps for the next meeting: the first meeting was about gathering all the problems together, the second meeting would look at steps to take etc.;

* We talked about the fact that many workers will be on holiday in December and that it would be a shame if the dynamic would be lost due to meetings being smaller during that period. One suggestion was to make a clear decision that things start again in early January and that in the meantime we can deal with individual grievances and smaller meetings;

* We created a WhatsApp group.

Apart from the big meeting we also met up with a maintenance worker and tried to support him and his workmates with a grievance. We hoped that this would raise our profile a bit, as he had worked in the plant for over 15 years and seemed well connected. But his co-workers, who were also affected, did not show up with him at the following meetings and momentum petered out.

We tried to arrange similar meetings around specific grievances with other groups of workers, e.g. the quality controllers who voiced particular concerns about having to oversee two lines for no extra pay. Unfortunately the QCs had no time or energy to meet separately. We had hoped that these smaller meetings could work in tandem with the big ones and create more mutual trust.

Between the first and the second meeting we were asked by one of the workers to accompany her to a meeting with management regarding the petition workers had undertaken independently. We decided that this would be too early and would put her at risk, as management would connect her with the union. In hindsight this might have been a mistake, as the worker (and her colleagues) might have seen this as a lack of support, despite our efforts to advise her regarding the meeting and explaining why we would not attend as union reps at this point. This was also a turning point in the sense that initially workers said they would not go in a small group to meet with management – and we encouraged them in this. Management addressed some (mainly Lithuanian) women directly, workers then decided to go in a group of seven, eight. In the end, either because ‘the Goan workers chickened out’ or because management refused to receive a bigger group of workers as representatives only three women went and were pretty disillusioned afterwards. They said that they felt left alone by their co-workers and didn’t attend the following union meeting. Management reacted to the petition by announcing to introduce a different clock-out system for breaks, to make things more ‘transparent’. We said: management ignored the workers’ letter with common demands, let’s put forward a letter as a union with at least half of workers as members – they cannot ignore this, as we can ask ACAS or other boards to address management formally.

Last, but not least we offered on-site childcare for workers who wanted to attend the meeting, taking into account that may workers have family duties.

/// Second meeting

We thought of the following structure for the next meeting:

* Handing out our list of typed up grievances from the first meeting;

* Highlighting the importance of the collective steps workers had already taken (e.g. their petition);

* Doing an IWW presentation about the union and why it was different to the bigger unions. We emphasised the fact that workers would have to take the lead and that we could support them;

* Photocopying their contracts to undertake research into possible illegalities by the company;

* Asking workers to keep a detailed diary of incidents, e.g. in case they are sent home unpaid (date, name of supervisor etc.);

* Talking about how we can put forward our demands, even without a formal union and how to back up demands without becoming targets (e.g. work to rule);

* Our options in terms of going for formal recognition and what that would involve, and how we could build up power on the shopfloor through collective actions;

* Short input from the Ferrari showroom cleaners about what they did and how they got better wages and conditions.

A similar amount of workers came to the meeting, though half of them hadn’t come to the first meeting, also meaning, half of the workers from the first didn’t come to the second. Unlike the first meeting, this time we ended up doing most of the talking. There were more men this time, whereas at the first meeting the majority were women. We asked why not more co-workers came and people mentioned family commitments and holidays as reasons, but also fear. People also mentioned that many workers have little knowledge of general union rights in the UK – we noted these various issues down to re-work our leaflets. We collected copies of the two different contracts to study them in detail.

We agreed to focus on break-times and being sent home unpaid as the main issues for the moment and put forward the proposal to first collect 50 signatures before handing in an official grievance. We discussed afterwards that it would obviously be easy to turn these workers’ complaints into formal grievances and to shower management with them – problem is that workers seem not really prepared for a more sophisticated response from management, e.g. to pay some QCs more or to shift trouble makers to other A1 sites. We wondered whether we had struck the right balance between being enthusiastic and encouraging, at the same time, being realistic about what management could do in retaliation and the fact that nothing would change overnight, or just by them filling out a membership form. There was a similar fine balance between, on one side, encouraging workers in their individual outrage, e.g. about the contract situation, and on the other side explaining to them that the law is, in many cases, on the employers’ side.

Even though we tried to stress that we need to start from a collective position, people still were quite focused on their individual/departmental problems e.g. one hygiene cleaner who said his shift worked harder than the other hygiene shifts because they had to deep clean machines and use chemicals – the insinuation being that they should get more than the others. We should maybe think about what our approach should be in this situation. Obviously, it would be better for everyone to fight together for the London Living Wage rather than a quid more for their own department/shift. We could have suggested this when we had these smaller meetings with them. At the same time, it would be good for them to try and stand up to management in smaller groups with workers who are all immediately affected by an issue in specific situations. We need to think about how to encourage this, while at the same time, trying to get them to see how they’re all actually facing the same problem, just in different ways and that if they want to fight together, they will need to focus on broader demands that affect all workers.

Regarding union membership: we handed out membership forms, but told workers to bring them back next time. We wanted to make sure that we had all their details – address and phone numbers of workers who signed up. Some people said that £5 monthly membership fee was too high. We decided that at the next meeting we would accept £1 as a symbolic membership fee and tell people that they could consider paying more once they see that the union is something that they are part of and that makes a difference in their lives.

It was great to have cleaning workers from the Ferrari showroom and UVW comrades at the meeting who could tell the A1 workers about their experience of taking on management. The fact that they are migrant workers themselves, who have similar problems regarding language and other barriers, made a difference.

/// Third meeting

While over 20 workers came to the first two meetings, numbers came down for the third – only around eight, nine workers turned up. This meant that our initial plan to break up into smaller groups of three – four workers and discuss more face-to-face fell through. Workers reported that management had spread rumours that people who join the union will be fired and that people are generally sceptical about what can be achieved. Workers who have been in the UK for a longer time said that the ‘recently arrived’ workers just want to keep their heads down and don’t understand their rights. They want immediate results, if possible through pressing a ‘legal button’ by someone who knows the law. Also workers said that certain ‘key figures’ had given up, which meant that other workers also got discouraged. Perhaps we should also have pushed for a meeting in early January, given that the holiday break left a bigger gap (over a month) between the second and the third meeting – we might have kept up more of a dynamic. We tried to fill the gap with smaller group meetings (QCs, maintenance) – but they were seemingly more difficult to arrange.

Eight workers signed membership forms at the third meeting, but we knew that we would have to rekindle some of the earlier fire, as only the maintenance worker came to the follow-up meeting a week later. The WhatsApp group didn’t really work, we received few replies, apart from Goan Catholic memes! We kept on calling workers individually and some said that they are afraid that things from WhatsApp would be passed onto management. A short reflection from a fellow worker after the meeting:

“Obviously, when we’ve gone from meetings with 20-25 workers to meetings with a near-total no-show, it’s easy to be dispirited. Perhaps we could have been faster in coming up with a detailed plan. However, I think overall we’ve been efficient, reliable and enthusiastic in all our dealings with A1 workers so far. There certainly may be truth to the workers being initially hyped-up and then less interested when they realised they’d have to put work in themselves. Management may have also done more to scare them then we might know. In any case, an organising drive in a factory this size, with these conditions and ethnic diversity is likely to take years. There’s still lots to play for so we should dust ourselves off and go back to basics.”

We decided to return to the A1 factory with more translations and more information on basic rights, also addressing the nightshift. We also went to the company’s second factory and the bigger warehouse near Heathrow airport which did not elicit any enthusiastic responses. We found out that the Bakers’ Union was present in the second factory, but that conditions were not much different.

We agreed to meet workers after their shift in a nearby cafe to collect membership forms, but although we reminded workers to bring their colleagues no one turned up. At this point it was clear that the mood had shifted.

At this point we were a bit demoralised. Workers at A1 were reluctant to proceed. They gave a number of reasons including a lack of trust that other workers would step up (“they say ‘yeah yeah’ but then they don’t do anything”); that the time is not right, that things will become more hopeful after Brexit and there are less workers around to plug the gap; that people were too scared; that people don’t have time to come to regular meetings etc. After a 2 month break we went back to A1 but focused more on leafletting the night-shift workers who had not been present at earlier meetings. We distributed a modified leaflet with basic information about unions in the UK. The response was very good. We gave out over 100 leaflets and workers were interested to hear that we had met with workers from the day-shift.

On our second visit with the new leaflet to night-shift, one of us wrote:

“The most promising people I spoke to were two Goans who were really pissed off and listed loads of problems – unpaid overtime, problems with falling sick and being unable to get home, no raise with the statutory minimum, the super fast line speed ‘killing their hours.’ They said they wanted to meet and would bring 10-15 guys with them. Also spoke to a guy called M. He said ‘his prayers had been answered’ because he’d been wanting a union to get involved for years. Another Goan guy said he’d heard about the day meetings with us through friends but said night shift can never make them. He said we should arrange a meeting at 9pm or 9.30pm somewhere close to A1 for the night shift. Seemed v angry and keen.”

We went twice more since then and we reckon things are still brewing. We heard of rumours that management paid a compensation for the day-shift for loss of break-time – which was one of the demands both workers’ petition and our leaflets focused on. We will try to organise a smaller meeting with four – five more committed workers and build things up slower e.g. maybe through offering specific organiser training sessions for the workers. We will also keep an eye and an ear out regarding disciplinaries and grievances, where workers might want our support – officially or not. We organise monthly general ‘social meetings’ in the area and invite our A1 contacts.

4. Conclusions and open questions

* Most of us think that despite the limited ‘success’, the effort was insightful. We managed to organise the stuff ourselves and with little resources. A paid-full time union organiser might have been able to be in front of the gates more frequently, but a group of 20 volunteers can cover a fair bit of time and space.

*This experience underlines the fact that the situation for migrant workers in particular in this ‘hostile environment’ is tough and we won’t build anything overnight. Yes, a spark might set things off, but we cannot bypass the day-to-day organising that requires a longer-term approach.

* Apart from migration, the nature of the work poses a challenge, as in the surveillance and control. In comparison, (many – not all, of course) cleaners in central London often have chances to discuss the work and problems and solutions together with their workmates out of sight of management.

* We were aware of the problem of not having a group of workers inside the workplace, but having to depend on getting to know workers through frequent visits. Most examples show that ‘cold organising’ is a difficult and time intensive effort. At the same time we learnt a lot during our conversations with workers. With even just one or two contacts and the name of the union spread amongst hundreds of local workers, some seeds might grow for the future. A1 showed that with a bit of luck we can be at the right place at the right time.

* As described earlier, the so-called ‘social leaders’ on the shop-floor – outstanding workers other workers tend to look up to – are often tied into the general hierarchy by being given middle-men positions. Having said this, our type of organising effort will rely on finding workers who are more committed and who are able to motivate other workers to get things going. We are aware of the tension between these two facts.

* We still face a classical conflict: for strategical reasons AngryWorkers chose jobs in bigger local workplaces (major food factories and retail warehouses), where mainstream unions are well established. We try to build independent ‘workers’ groups’ and newsletters and at the same time see what is and isn’t possible inside the existing unions. There is little scope for official IWW involvement at this point, as it would just be seen as another act of union competition.

* During our organising drive we were unsure how much to push individuals or a group of workers. How many times do you call a worker or invite a worker before you accept that they are not interested? How much do you encourage a group of workers to take steps when you see that they already have a full plate of problems. We always emphasised that this is up to the workers and that workers can do a lot of things at work without becoming targets. We didn’t shy away from providing a fair bit of service, despite our critical attitude towards ‘service unions’.

* At the same time, in terms of the bigger picture, what we need are examples that can inspire other workers. If there was a successful strike in one of the hundreds of medium-sized factories and warehouses, this could spark an enormous dynamic! This is so palpable and therefore we can understand comrades who want to push this example into being. However, we run into a problem when a minority of workers want to act in a larger workplace because chances are that they will become isolated and lose their jobs. In Italy they managed to break this dynamic by having a large Left presence as external supporters. But it is difficult to get people to come, or stay interested in these western hinterlands… Although inspiring, the current examples of migrant cleaners organising in central London happen in a significantly different context (e.g. on more politicised and public campuses).

* We were caught in a contradiction: our main way to show support for workers and build trust seems to be to help them with legal matters and grievance/disciplinary proceedings. At the same time this re-enforces their idea that someone who knows about local law can do some magic trick for them.

* We should encourage a more open exchange of workplace and organising experiences within the IWW and other smaller unions like the IWGB and UVW. We are more often than not only presented with the final and official outcome of organising efforts – reports of problems and failures are often not shared openly.

* We were cautious to avoid a union competition when we heard that one of the mainstream unions was already present. At the same time we should be confident enough and ask the question: workers here complain about the conditions, you have recognition here, so what is your plan? More importantly, workers themselves should discuss what they want to do – if the existing union is not willing to support them we should encourage independent action.

* In the long run we have to transition from occasional leafletting to continuous presence in the area: solidarity networks, drop-ins, workplace newsletters and working class newspapers are essential in order to create a wider structure of working class self-organisation. (While writing this review we were contacted by truck drivers of Punjabi background through our solidarity network, who want to organise with the IWW)

* We should also re-discuss the potentials and limitations of salting, of going to take jobs in workplaces like A1, L1 etc. in order to help organising. We hope to be able to present a paper on the issue soon.

———

5. Appendix

a) Short summary of the reports after team visits at the other companies

b) Write-up of grievances at A1

c) Leaflet A1

a) Short summary of the reports after team visits at the other companies

*** E1 – Ink-cartridge re-filling factory

E1 employs around 150 mainly female workers of Gujarati and Lithuanian background, who re-fill ink cartridges. Most workers have been working there for five, ten years or longer and are on permanent contracts. Management is of the paternalistic and patriarchal type. The company expanded during the early 2000s, employing up to 250 people. Colleagues said that in their heyday they re-filled 15,000 cartridges a day: the UK consumes around 45 million cartridges a year and with 250 people and basic machinery you can recycle around 4 million of them. While the company clocked £2 million profit per month, the wages of the workers did not increase. During the late 2000s the competition from re-filling factories based in China grew considerably, thanks to internet retail and logistics chains. By that time the upper-management had diverted a fair amount of business profits into real estate and kept the business ‘ticking over’ – the rounds of redundancies and spells of short-time work became more frequent. By the mid-2010s there were only 150 people left in the ink department.

Their main concerns are the low wages and the fact that during periods of low work volume during summer months workers are sent on short-time and suffer wage loss. There has been resistance of a group of ten, twenty workers to sign a new contract which inscribed the right of the company to sent people home unpaid. Some of the male workers in supervisory positions had been in touch with GMB union, but this didn’t lead to any results. One of us had worked in the plant for about a year and we were in close touch with two male workers, but they were reluctant to take on a more active role, saying that ‘the women are just waiting for their retirement’.

In our first leaflet we addressed the main issues and the fact that workers could do with a collective response next time management introduces changes to contract:

“We managed to catch two workers coming from night-shift, there are only 10 people on nights – one of them started recently, but he seemed interested. Most departments and language groups got enough leaflets to circulate them around (Moroccan men in maintenance, Lithuanian women in packaging, Gujarati and Goan women in production, Goan men in the warehouse). Response was positive, though less enthusiastic by some Gujarati women. Only two refused to take a leaflet, and they were quite specific that they don’t want to have to do anything with a union. I guess the talk of a union has been around for a while. The only white British shop-floor worker – he is called the ‘pitbull’ because once he engages you in a conversation he would not let go – talked general bullshit about ‘for the Indian women worker this here is only social activity, they don’t need the job, they all have houses and money’ etc.”

One of our E1 contacts replied:

“So I have been trying to ask a few guys amongst the staff of how they feel about it but surprising enough most of them are very sceptical about it. A few of them are already a member of another Union and because they haven’t had a particularly good experience with that one therefore they don’t see IWW being any different. But the majority of the staff have worked for E1 for well over a decade and many of them are relatively close to retirement as well so they just want to see their time out without any trouble. On the top of that the management got hold of one of your flyers which didn’t go down well with A. [CEO] to say the least. Today he issued a letter to the staff to encourage every one to approach the management with confidence if you have any problems, concerns etc. instead of joining any Union.”

The letter said:

“Response from A. [name of CEO] regarding International Workers of the World (IWW) leaflet

[…] I am sure that any of you who were interested in what you read will have found out more information about the IWW organisation from the web. The IWW has been in existence since 1905 but has always had a small following (just 3,742 members in 2016) As stated on their website, “the IWWis a revolutionary global union” and prides itself on “autonomy, common militancy and solidarity”. This is far cry from the values of E1 and what we do together as a working team. Instead of taking a militant stance, we have always encouraged open conversation and resolution, not revolution. […]”

In our second leaflet we addressed the fact that some workers had bad experiences with main-stream unions and emphasised that with the IWW decisions are made by workers themselves, supported by other workers. We also made clear that E1 management often just presents workers with their decisions and that their talk about ‘conversation and resolution’ is hypocritical. A union would be a vehicle to first discuss things amongst ourselves and then present management with a common stance. We offered to meet workers after work. During second distribution we had short conversation with a young Goan warehouse worker, he is unhappy about the wages, which are still below £8. Another warehouse worker promised to get in touch. The big manager came out after 5 min and started filming. Workers didn’t get in touch, but management reacted internally.

From our E1 contact:

“With the festive period right upon us I thought I’d give you a little update of what’s going on at E1. You may not have had a huge amount of interest from the guys here at E1 with regards to the Union, yet by the looks of things your “antics” had a good impact on the management which resulted in some positive news for us. Just a few days ago we had a meeting held by A. [CEO] (a kind of staff update of how the business is doing) where he explained that the company has come a long way since 2015 when the business was on the verge of bankruptcy. So he thanked everyone for our hard work and he backed up his appreciation by giving £100 bonus for each member of staff. This is the first time in 8 years that we have received any sort of bonus. Further more he promised that the salaries and performances would be reviewed individually and the ones that have more responsibilities and the overachievers are going to be rewarded in terms of pay rise. Moreover every quarter of the year there will be meeting where representatives from each department (from the staff) can take part and raise their issues, concerns, ideas for improvement etc. directly to him.”

We went another time to leaflet in a bigger group and invited individual workers via phone contact to a meeting with A1 sandwich factory workers, but with no result. We maintain individual contacts.

*** K1 – Crisps factory

The factory produces crisps for most major supermarkets, employing up to 1,000 workers, including many workers from temp agencies. Although some of us work in a ready-meal factory next to K1, we actually knew very little about the conditions and had no stable contacts inside. Workers complained about low wages, compulsory Saturday shifts and unsafe working conditions – there had been bad accidents at the frying stations. Most workers are from Gujarati and Romanian background. Only after our first visit we found out that the GMB has individual members there. The GMB had distributed a leaflet after an accident criticising that management had called a taxi instead of an ambulance. We addressed these concerns in our leaflet and also made clear that we don’t make a difference between permanent staff and agency workers. Initially we only had leaflets in English and our team-members could only address Polish workers in their mother-tongue. Translating leaflets and having native Gujarati speakers during following visits made a difference:

“V., A. and me visited K1 for the first time today. We arrived at factory’s gate at 2pm. At around 2.30 workers from Response agency started gathering to sign in for a shift. Mostly Gujarati speakers and some Romanians. Had few conversations.”

“V., J. and I me visited K1 again. This time we had English, Romanian and Hindi copies of the leaflet. We distributed around 70 English, 50 Hindi and 30 Romanian copies. Spoke to two Polish women, one said that there were people from other unions distributing flyers before (GMB?), second one said that everyone is scared to lose their job and all just wait till end of the shift everyday.”

“We were told by one Hungarian guy that a Romanian worker might get in touch cause he got injured on that same day. The Hungarian one was particularly enthusiastic and started explaining people what the leaflet was about. Romanians were positively surprised to see leaflets translated into their language. One guy, possibly British Afro-Caribbean stopped by to say he would like to get involved with a union and “help people, defend workers’ rights”.”

“I spoke with Romanians (in Italian, it actually worked out:), Moroccans, Hungarians and Gujarati speakers. Some were interested, got the idea that if we speak with the management they would listen more. Some were also in favour of petitions to voice their demands. Others were skeptical saying that management would fire them if they dare to stand up for their rights. Most people complained about the minimum wage, so I told them about the cleaners’ case and mentioned A1 workers as a case of self-organisation. Ethnic divisions seem to be an issue in the factory, Eastern Europeans were blaming the “Indian management” and saying there were too many South Asians workers. About injuries, they confirmed that no one cares nor they would call an ambulance if you get seriously hurt (although none of them had been seriously hurt apparently, only minor cuts on their hands). One worker asked how he could get his taxes back, I honestly didn’t know what to tell him other than check HMRC. Vanessa fittingly said we should tell them to come to a drop-in session anyway, as there would be people who are able to help on tax issues anyway.”

“Me, V., H., A. and J. went to K1 again, today at 2.15pm. H., who is Gujarati speaker, has agreed to come along with us and talk to the workers. We gave out around 150-200 leaflets in Gujarati, Hindi, Romanian and English. It was good time to approach workers as they were gathering outside before and after shifts. People seemed to be more keen to talk to us than before. Spoke to group of Polish women, they said that ‘everyone is racist’ and they don’t see the point of getting together, but took leaflets.”

We organised four, five visits and made various attempts to invite individual workers to our weekly drop-ins – with little results.

*** P1 – Logistics warehouse

The P1 warehouse is situated close to other warehouses we either want to organise around or we work in ourselves, so we thought of giving it a go despite not having much insights or contacts. As the name suggests, the warehouse mainly shifts pallets between trucks – apart from office staff there are only 50 to 60 lorry drivers (plus self-employed drivers) and 30 to 40 forklift workers, mainly from eastern Europe. It operates 24 hours, seven days a week. The company is operating internationally, with warehouses in other European countries. There is a lot of pressure on drivers, they sack people for minor mistakes – while increasing the number of self- employed drivers. They pay a bonus if workers go on a second round (20 pallet plus), but they pay the bonus arbitrarily. They also give drivers unequal routes, which causes frictions. The fork-lift drivers are over-worked, which leads to delays, which makes it difficult for the drivers to get their bonus.

We gathered this basic information during our first visit and used it to re-write the leaflet, incorporating these particular grievances. This was well received.

“One very vocal Polish driver who had been working there for 12 years was very keen to organise and we took his number. He suggested we host a meeting at P1, he seemed very confident that this would okay. He said there may be an issue with high turnover and agency staff that could make organising difficult. He also said there weren’t common areas, people just come in, get their delivery list and leave again – not much cohesion.”

“We spoke to guys from Hungary and Bulgaria who were also keen and had worked there for some years. Most of the Eastern European workers were very welcoming and greeted us with handshakes and were interested in the union. There was also a Romanian and Lithuanian, someone from the West Indies, loads of different nationalities. The Eastern Europeans at least, seemed to have good communication with each other. One had had a bad experience with unions in the past and said he ‘shits on them’. One suggested our time would be better spent at DPD in Southall. The few English workers we met were quite dismissive and hostile. Some worked as self employed drivers.”

“6.50, we met a few people from last week again, they were friendly. I spoke to the Hungarian guy when he was in his cab, he said “there’s no equal opportunities here” which meant some people get more work and better work arbitrarily. He also said he was nervous because there’s cameras everywhere, even in the cabs. Another guy called me over and asked for a leaflet. He told me yesterday someone got fired unfairly and they both would be interesting in meeting us. I gave him my number. We spoke to a black guy in his cab who said he isn’t interested in the union because he’s scared of losing his job. No chance to reply because female supervisor in orange fluorescent came out of warehouse and told us politely to go away. We went home.”

We were able to meet one of the drivers from Romania who got dismissed for allegedly not securing his load properly. We sat together and wrote a letter to management pointing out that this could be unfair dismissal due to discrimination – which was a bluff and management called it a bluff. We had hoped that by being able to help this driver we could create more trust amongst other drivers. This didn’t work out. We managed to gather a fair amount of phone numbers from drivers, but didn’t manage to convince them that it is worth meeting up. Given the lay-out of the warehouse it was difficult to get in touch with the fork-lift drivers. In Italy, P1 workers organised industrial action together with Si Cobas, we thought about trying to get a solidarity message from Italy, to boost the morale in London, but that didn’t materialise. There are still individual contacts, but they are sporadic.

*** W1 – Warehouse and packaging plant for fruit and veg

W1 packages veg and fruit for all major supermarket chains. Most of the veg and fruit comes in passenger machines (Egypt, Kenya, Jamaica etc.), arriving at Heathrow airport nearby. W1 has contracts with around 14,000 ‘independent’ small farmers in Africa and has their own agro-farms in India. There are around 180 workers at W1, all permanents, working on two shifts. Around 70 per cent are women, most workers are from Gujarat, Goa and Tamil speaking. It is mainly line work, standing up continuously. Unloading the air-containers is heavy and dangerous (heavy boxes taken over-head with vacuum crane). Workers are supposed to stay till work is finished, up to 14 hours. Many workers have been working there for five years or longer, still they get the minimum wage. The general level of english is pretty low. The warehouse is located opposite of P1, were we are in touch with drivers. One of us had worked in the warehouse briefly and we are still in touch with an ex-colleague, but he wants to keep low profile. We visited W1 several times, but workers seemed intimidated and in a rush. Only after four visits we managed to distribute a translated leaflet.

“Around 50 workers went past in twos and threes. Pretty much everyone at W1 took a leaflet , but we only managed about 4 conversations. One in Portuguese (with a probably Goan lady) the rest in Hindi. Workers were pretty much all of South Asian origin and spoke next to no english. I didn’t feel like it was a very productive hour at W1, it’s very dark because it’s before dawn, and people seem suspicious of us.”

“I met a woman at the W1 gates at about 7.05. She was late for her shift but was still keen to talk. She is in quality control so she said she earns more. And works maybe two hours less a day (but still 10 hours if I understood correctly). However she was really interested in the union and and keen to meet up outside of work to talk about it. Will message her today. Feels like a bit of a breakthrough.”

“Only spoke to night-shift guys, they are pissed off about 12-hour shifts and low night-shift bonus (they get £7.95). I have one guy’s phone number, meaning that we have one number from day and one from night-shift. Will contact them both tomorrow and see if they are up for meeting us…”

We managed to speak with one of the workers on the phone, they wanted to know if something can be done about the fact that management refuses to give more than three weeks holiday. We tried to arrange a meeting, but it fell flat. We try to maintain individual contact.

*** S1 – Sofa warehouse

S1 is a sofa and furniture store, now taken over by DFS. The warehouse in west London employs around 50 people, many from agencies, plus van drivers. Most of them are from eastern Europe and of Afro-Carribean and African background, all male. One of us had worked in the S1 store for a while, but was made redundant during restructuring. There was no union present, so S1 installed a phoney ‘staff forum’ to pretend that there was some sort of consultation process. Our friend heard from S1 workers employed in the nearby warehouse that there are a lot of arbitrary (and racist) disciplinaries and warnings issued by management. Workers representatives are told that they are not allowed to talk during disciplinary meetings, which is not correct. On top of this, delivery workers often have to work unpaid overtime to be able to finish their rounds. We addressed these issues in our first leaflet.

“It looked like some agency workers, but not many, where coming in later. They seemed receptive to the idea of the union and all of them took the leaflet. We could speak with some of the more veteran workers that where going out the depot with the trucks. They listened more when I told them that I was in the store and was seeing all the disciplinaries.”

“Because of conflicting information and to be completely certain of shift start times we got there for 4.15am expecting some workers to start coming between 4.30 and 5am. We soon found out that this day was special because a series of managers turned up for what we later learned was a meeting with workers to discuss pay and overtime rates, presumably in advance of the Christmas season. A manager had travelled down from Manchester for the occasion, too. One boss told us forcefully that unions are ‘not recognised by this company’ and insisted we not give leaflets or ‘harass’ the workers or he would call the police. First workers entered at 5.30am, and a total of 25 workers. Reception from the workers was positive and a couple were confident, with one saying that the meeting about pay had been called because the workers asked for it, and another insisting that we should be allowed inside to talk at the meeting. They said that the meeting had been positive for the workers but the bosses also told all staff not to talk to us in the future.”

“The quality inspector, J., has been working at S1 a few weeks and is angry about a supervisor’s disrespect towards him, and the supervisor’s racist attitude towards a colleague. J. is under investigation for allegedly being late on one occasion. He has to travel 2 hours from his home outside London and arrive for a 5.30am start. J. expects to be disciplined, and we advised him to challenge any management attempt to do this without giving him a formal letter or without offering him a chance to be represented. He was as, if not more, concerned with the supervisor’s arrogance, and for now, we advised him to keep a note, date and time of incidents of abuse to able to use the evidence against the supervisor later.”

“So far though, the workers seem quite alienated or disconnected from each other, with the drivers maybe knowing only their truck partner well, while the mix of permanent and agency workers in the depot means there is some unfamiliarity between workers which would need to be overcome.”

We didn’t manage to organise a bigger meeting, but try to keep in touch individually.

*** L1 – Industrial laundrette

The laundrette employs around 150 workers per shift, around 10 to 20 per cent of them hired through agency. The company supplies restaurants, gyms and hotels in London. Most of the workers are women from South Asia and ester Europe. Wages are around the minimum, even for permanent workers who have been employed for years.

“The GMB is apparently present, though many seem to be unaware of this. One driver said “We definitely need a union in here”, indicating he didn’t know there was one even operating inside. When I asked one woman if the GMB helps, she replied “10p above the minimum wage – do you think they help?”.”

This also meant that workers were generally a little weary when we said that we are coming from a union.

“After all the workers were gone, two bosses came out to bully us. They tried to act intimidating and accused us of “harassing” the workers – according to them one of the workers felt harassed by us giving a leaflet. They also told us the information on our leaflet was “incorrect” and “defamatory”, that they will contact the “person who is responsible for this”, threatening us with “solicitors” and saying we had trespassed private property (the roads are indeed private)… At least they told us they have 500 employees and all are union members, though the latter claim is clearly bullshit.”

We asked a GMB organiser, who is an old lefty and he confirmed that there are around 120 GMB members at L1 and that they have a recognition agreement. We discussed what this fact means to us: conditions are bad, management and union have an agreement, meaning that there is no legal chance to enforce a recognition agreement even if you organise the majority of workers – see summary of discussion in the final conclusion bit of this text. In this specific occasion we decided to try and get in touch with the GMB reps in the factory, to talk about what workers had said to us (low wages, work pressure etc.) and to ask them what we can do about it. The GMB organiser tried to facilitate an exchange, but the GMB factory reps refused to meet. We distributed leaflets a second time and then decided to focus on the nearby A1 factory.

———

b) Write-up of grievances at A1

*** Main problems at A1 – Notes for workers from meeting, 18th of November 2017

1) Wages

Wages in general are below the London Living Wage of £10.20.

2) Line Speed

The line speed often exceeds limits which would maintain workers mental and physical health. Production targets are often set too high, resulting in necessary cleaning of belts and machinery being neglected. Quality Controllers are told off for stopping the lines when they notice quality problems, which are largely due to excessive work speed.

3) Disparity of conditions between employees with Superior Foods and Food Partners contracts

During a meeting in 2016 management promised to equalise conditions of A1 employees with Superior Foods and Food Partners contracts. This did not materialise and workers with Food Partners contracts and newly hired employees still have significant disadvantages. Unlike workers on Superior Foods their breaks are not paid (which amounts to £27 a week), they don’t receive 1.25 payment for overtime after 45 hours weekly working time and 1.5 payment for work on their days off or bank holidays. Back-payments are given arbitrarily.

4) Workers do not get the statutory break time

Management asks workers to clean machinery and get in and out of protective clothing during their break time, which results in substantial cuts to their actual break time. This is worsened by queues on the way out from the shop-floor. Management cuts 15 min from workers wages if they arrive 2 min late from their break. Workers also report about being harassed when they ask to go to the toilet. If necessary ingredients arrive late, workers have to make up for it by working continuously after their arrival, without being given their breaks. If management orders overtime and shift times exceed 10-11-12 hours workers are often not granted a third break.

5) Workers are not paid their contracted hours and forced to take holiday

Despite having contracts which state the weekly working times workers are sent home unpaid with short notice. Sometimes this results in weekly working-times of less than 35 hours. If there is not enough work workers are forced to take holiday or otherwise they are not paid for the day off work.

6) Shift-times and overtime are announced too short notice

Start of shift times is often announced only the day before and only through notifications on the shop-floor. Workers who are not at work that day do not receive this notification. Workers are forced to work overtime short notice. Sometimes the statutory rest time of 11 hours between shifts is not given.

7) Holiday payment does not reflect previously worked hours

Holiday pay is only paid at the basic hourly rate, whereas it should reflect the average amount of hours worked over the last 12 weeks period.

8) Workers cannot decide about their holidays

Management only grants two weeks holidays on stretch, which is not enough for longer travels, e.g. to India.

9) Workers are being shifted between departments arbitrarily

Maintenance workers have been shifted from the maintenance to production department without consultation.

10) Pay grades are set arbitrarily

Maintenance workers with the same formal skill set are categorised as either multi-skilled or maintenance assistants arbitrarily.

11) Workers have serious health and safety concerns

Management ignored complaints about cold and draft conditions several times. Management ignored complaints about inadequate food wear several times. Trays with ingredients are often overloaded, resulting in workers having to lift up to 100kg. Cleaners are not given enough time between shifts to do their job.

12) Doctors notes are questioned and workers disciplined for being off sick

Doctors notes are not being respected. Management indicates at meeting with worker that they will influence the decision of the ‚independent‘ assessment doctor. Workers who have taken their annual holiday are told that “you can’t be sick for the next three months now”.

13) Workers feel disrespected

Overall management treats workers with disrespect. If workers raise concerns they are told to “look for another job”.

c) Leaflet A1 – Next page

A1 workers in Wembley: Let’s fight for £10 an hour!

– Report from A1 workers’ meeting in Southall

We are part of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a different kind of trade union. You make the decisions and we support you – for better pay and more justice at work. We help people if they have problems with management, landlords or the immigration office. At the moment we are getting in touch with workers at a few companies in this area.

We have organised meetings with A1 workers in Southall. They had written a petition to management signed by about 100 workers. Their main problems are:

* shift changes with short noice

* if there is no work, people are sent home unpaid or are forced to take holidays

* often shifts are too long, with no extra breaks

* workers are on different contracts: those on Superior Foods contracts get overtime bonus and paid breaks, those on Food Partners and A1 contracts don’t

* QC workers often have to work two lines at the same time

* hygiene workers don’t get enough time to finish their work

* maintenance workers are shifted from maintenace engineers contracts to maintenance assistant contracts

We discussed these things at the meeting. We also discussed that it is important to create links between A1 in Southall and other A1 sites. We visited the warehouse near Heathrow and now talk to you in Wembley.

What can we do..?

Our goal is to ask A1 to pay you more and listen to what workers have to say.

• Meet us to discuss things face to face. Bring one, two, three colleagues you can trust.

• There are various things a group of workers can do at work to put pressure on management without becoming a visible target.

• If just 10% of A1 workers at this factory join the union and 50% of them agree that the union should negotiate for better wages, we can address A1 management directly to ask for better pay.

The IWW is different from other unions…

• We are not here to get your membership money

• We don’t have paid staff or expensive offices

• We don’t tell you what to do, but listen what you want to do.

How to keep in touch…

Please send us a text or write us an email. Tell us what you think, ask questions. Tell us when and where we can meet in Wembley or somewhere close to where you live.

You can also come to our Solidarity Network for advice and support. We meet regularly between 5pm and 6pm:

First Monday of the month: McDonalds Greenford, Retail Park, UB6 0UW

Third Monday of the month: Asda Café, Park Royal, NW10 7LW

Fourth Monday of the month: Poornima Café, 16 South Rd. Southall, UB1 1RT

07544 338993 / westlondon [at] iww [dot] org [dot] uk / www.iww.org.uk

Dedication

Dedication